What Doctors Don’t Tell You Australia-NZ – February-March 2022

English | 86 pages | pdf | 45.69 MB

A DIET FIT FOR A MONKEY

What is the best diet to follow and foods to eat to regain or maintain optimum health? The equivalent of the Brazilian rain forest has probably been leveled to print the books attempting to answer just that question.

But confusion still abounds. Should you go Paleo or vegan when you are ill? And what are the best foods to prevent or heal cancer?

To find out, we need to take a tip from bears—and monkeys and rats and most of the animal kingdom.

After witnessing sick bears eating the roots of Ligusticum plants and getting better afterward, North American Native Americans gave the plants a name that means ‘bear medicine.’

Most conventional scientists have disparaged anecdotes such as these, putting them down to myth—until recently. Animal behaviorists have discovered that animals do indeed appear to have a natural instinct, across species, for determining which plants can be used to stay healthy or heal different diseases.

Animal behaviorist Dr Cindy Engel spent years gathering scientific evidence that animals self-medicate, much of which she poured into her book Wild Health (Houghton Mifflin, 2002). In her research, Engel discovered that animals instinctively know how to maintain optimum health. Given a smorgasbord of choice, animals like rats, for instance, will choose a nutritionally balanced diet. A number of species even know to make compensatory choices when the food supply changes with the season.

For instance, she says, deer graze on grass in summer but switch to ivy and holly when the grass dies back. Similarly, when the energy content of food drops in winter, animals like the

Madagascar primate aye-ayes will double their intake; before droughts, camels and rhinos will switch to eating foods rich in salts and water.

What is also remarkable, however, among all species, is their instinctive sense of extraordinary nutritional needs. Animals like birds and squirrels will change the fat content in their diets before migration and hibernation, respectively. And when their nutritional needs increase, such as during pregnancy, they increase their consumption of mineral-rich foods.

When moose and deer need to grow antlers, their bodies raid the calcium and phosphorus from their bones to feed.

The animals would then develop osteoporosis if their diets weren’t extraordinarily mineral-rich, and therefore, because soils are often so depleted of these minerals, the animals will resort to chewing on cast-off antlers, chewing soil from around decomposing bones or eating salty fish.

Numerous other studies show that many vegetarians among the deer family become carnivorous when necessary, and animals that are ordinarily conservative in their diet will become more adventurous when deprived of a particular nutrient.

Perhaps more extraordinary is evidence suggesting that animals know how to self-medicate against parasites, infection, skin conditions and poisons. Engel’s data show that animals have learned which substances—such as clay, soil and charcoal—can absorb and neutralize particular plant toxins.

They understand how to deal with certain pathogens—either by increasing body temperature or, in the case of the honeybee, by coating the hive with propolis, a potent antimicrobial.

Engel has also uncovered ample evidence that animals rub bioactive compounds into their fur or skin to discourage unwanted insects, ticks and mites.

The American evolutionary ecologist and conservationist Daniel Janzen began collating evidence that animals somehow are able to differentiate the thousands of toxic secondary compounds in plants that kill internal parasites.

For instance, a number of species, including rhinoceros and wild bison, feast on a certain bark known to be toxic to the microbes that cause dysentery.

Even animals in captivity often have a native sense of self-medication superior to their doctors. In one instance, a captive capuchin monkey that had a severe skin infection did not get better until it was given access to tobacco leaves (which contain nicotine, a potent toxin). Rubbing the leaves on the affected area cured the skin condition permanently.

Although animals are supremely good at using food and natural substances to heal, humans seem to have lost that instinctive sense of what is good to eat even to maintain optimum health.

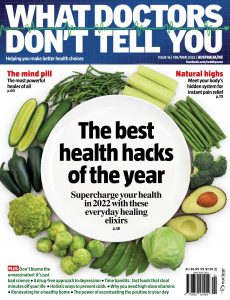

That’s why, to get this January off to a healthy start, we want to reinvigorate your intuitive sense of healing foods by offering our Superfood Diet, which includes the best regimes and the best superfoods for preventing a vast number of diseases, from high blood pressure to cancer (see page 38).

There are hundreds of superfoods containing extraordinary substances that can prevent or heal a vast number of diseases. Just four teaspoons of mushrooms a day can nearly halve your chances of getting cancer and also cut your chances of suffering from depression, for instance. Avocados contain a substance called avocatin B, which can prevent type 2 diabetes, help you lose fat around the middle and even prevent leukemia. Green leafy vegetables have been demonstrated to keep your brain sharp and your muscles strong into old age.

Conventional medicine has its place and is often peerless when it comes to emergency or acute medicine, but it fails miserably, in the main, when solving most chronic illnesses. Natural substances, on the other hand, contain complex, synergistic healing compounds that even the most sophisticated drug cannot hope to mimic.

To stay strong and healthy in 2022, the answer is quite simple: do what the monkeys do. Follow a Superfood Diet fit for human beings.

Download from: