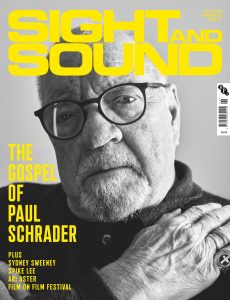

Sight & Sound – June 2023

angielski | 117 pages | pdf | 23.12 MB

Welcome at Sight & Sound Magazine June 2023 Issue

“For seventy years the SIGHT AND SOUND Magazine POLL has been a reliable if somewhat incremental measure of critical consensus and priorities. Films moved up the list, others moved down; but it took time. The sudden appearance of ‘Jeanne Dielman’ in the number one slot undermines the S&S poll’s credibility. It feels off, as if someone had put their thumb on the scale. Which I suspect they did. As Tom Stoppard pointed out in Jumpers, in democracy it doesn’t matter who gets the votes, it matters who counts the votes. By expanding the voting community and the point system this year’s S&S poll reflects not a historical continuum but a politically correct rejiggering. Ackerman’s film is a favorite of mine, a great film, a landmark film, but its unexpected number one rating does it no favors. ‘Jeanne Dielman’ will from this time forward beremembered not only an important film in cinema history but also as a landmark of distorted woke reappraisal.” [sic)

Paul Schrader is a complex man. On one hand, he is an anthropologist; his understanding of ‘God’s lonely man’ – through works such as Taxi Driver (1976), American Gigolo (1980), The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), First Reformed (2017) and The Card Counter (2021) – second to none, as much a chronicler of American masculinity as Mark Twain, John Steinbeck, Cormac McCarthy, John Ford and Norman Rockwell. On the other, he is a man using ‘woke’ as a pejorative to dismiss a shift he does not approve of, feel comfortable with, that distorts his understanding of the world. In writing the above comment on Facebook in the wake of the Sight and Sound poll results being published in December last year, he positioned himself with a shrieking mass suspicious of change, smelling tokenism, wokeism or sinister manipulation, often a poisonous cocktail of all three, wherever they poke their noses. And in his righteous irritation he was wrong. While the electorate was expanded, the points system didn’t change. Every vote in the poll has always counted for one, right back to the first instalment in October 1952, a few months after Schrader’s sixth birthday. There was no “thumb on the scale”. Like all good conspiracy theorists, though, he’s unshaken in his belief, six months after the fact.

It would be easy to dismiss Schrader as yesterday’s man, but that would be as misguided as his views on the poll. His work continues to be confrontational and provocative, grappling at its core with identity and moral decay. His latest film, Master Gardener, completes a thematic trilogy, alongside First Reformed and The Card Counter, that Schrader calls his “man in a room” movies. These are films that have, in his seventies, positioned him as director first, writer second in the consciousness of cinephiles, after being defined for so long by his frequent collaborations with Martin Scorsese. He lays pain bare on the screen, asks questions of

the universe and is the antithesis of the 21st-century American hardman, the Trumps and Proud Boys of a fractured America, proudly ignorant and deliberately blinkered. He’s a heavyweight of observation, like Norman Mailer, seeing conflict everywhere. Mailer famously once said, “When two men pass one another in the street and say ‘Good morning’, there’s a winner and a loser.” For Schrader, it’s not so much two men who pass each other, but two ways of life, outsider and institution. Scorsese was the ego to Schrader’s id during their partnership as writer and director as much as De Niro and latterly DiCaprio have been Scorsese’s alter egos on screen. But while Scorsese draws primarily

on literature and memoir as source material away from Schrader’s pen, building epic worlds of crime and punishment to convey his morality plays of men and their questions, Schrader remains insular, employing a more direct line to God. He is fallible,

a contradiction, combative, righteous. He has built a following of young acolytes on social media who lap up his invective. When he lets loose, he’s often right. When he’s down on things, it’s often for good reason. “More and more, you have cinema that is made for suspended adolescence,” he tells Erika

Balsom in our cover story on page 26, “the kind of movies that you liked before you went to college, before you became an elitist.” Balsom notes in her introduction to the feature, “Today, the writer-director is as prolific as he has ever been. The broken-down horse called movies keeps limping on and Schrader is still astride it.”

This is a good thing. He may be cantankerous and perhaps, at times, has the wrong target in the crosshairs, but he’s a symbol of cinematic purity who understands film as art, as fable, as allegory for a deeper, transcendental message. A New Yorker profile earlier this month claimed,

“Three times, when he’s had a film coming out, the distributors have asked [Schrader) to stop posting on Facebook, where he has a tendency to make impolitic comments.” It’s what makes him Paul Schrader. We won’t take it personally.

Mike Williams

@itsmikelike

Download from: