Claremont Review of Books – Spring 2023

English | 329 pages | pdf | 3.94 MB

Not for a long time—if ever—have American conservatives had a string of favorable decisions in the Supreme Court such as they enjoyed in the 2021-22 term. We are used to celebrating, faute de mieux, smart, heroic dissents by one or two courageous Justices, trying to claw back some of the ground lost to a rampaging majority. Such isolated dissents we had to content ourselves with not just recently from the stalwart Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito, but also going back 60 years to when Justices Felix Frankfurter and John Marshall Harlan found themselves disagreeing, unexpectedly and increasingly, with their colleagues. It took those dissenters a while to realize that Chief Justice Earl Warren and his fellow “activists” (too innocent a term, but it came to be applied) on the Court were not out merely to end segregation, which certainly needed ending, but also to revolutionize American constitutional law, and with it America.

Young conservatives today are not in danger of forgetting, because they are too young to remember, how radical were the Warren Court and its successor, the Burger Court. One by one, legislative redistricting, libel law, prayer in schools, obscenity law, the death penalty, abortion, criminal procedure, and many other traditional objects of American legal and moral regulation were overturned or substantially recast, not by elected politicians but by the Justices they had carelessly, and in a few cases malignantly, elevated to the Court.

Much of the change in mores we signify when we speak of “the ’60s” proceeded from the courts, and persisted well into the judiciary’s decisions in the 1970s and ’80s. Both popular and judicial opposition was gathering by then, but it took conservatives a long time to realize just how prepared, principled, and persistent they would have to be to close this chapter and open a new one in American jurisprudence. If you compare the Supreme Court appointments of the Reagan Administration with those of the Trump Administration you will see the difference. Reagan got lucky with Scalia and unlucky with Robert Bork (who in his confirmation hearing got “borked”), but Sandra Day O’Connor (the first woman named to the Court) and Anthony Kennedy were unremarkable judicial moderates suitable for quieter times, perhaps, but not for the epic clashes of this age. President Trump came into office under the tutelage of Leonard Leo and the Federalist Society, whose very names bespeak a concentrated awareness of how wrong things had gone with the judiciary. Trump profited from their seriousness and his own desperation, vowing to appoint Justices who understood the fight they were in, and who were willing (to mix metaphors) to steer quickly toward constitutional sanity. He benefitted, too, from Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s tenacity in refusing to accede to outgoing President Obama’s demand to name the late Justice Scalia’s successor. Death was kind to Trump again, stealing Ruth Bader Ginsburg away while he and not Obama was in office to appoint her replacement.

As a result, then, both of accident and preparation, Trump was able to name three Justices in short order—Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. These three gave the country

for the first time a bench of six conservative Justices, from whom a changing team of five could be fielded for even the most controversial cases. President Trump deserves enormous credit for taking advantage of this opportunity, or series of opportunities. He didn’t blink and he didn’t bungle.

It’s very probable that the repeal of Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the blow against the administrative state’s pretensions in West Virginia v. EPA, and the expansion of religious liberty in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (the case of the praying football coach, as it’s likely to be remembered) will amount to a turning point. Throw in next term’s likely repeal of affirmative action in Students for Fair Admissions v. President and

Fellows of Harvard College, and these cases could mark a real annus mirabilis in the recovery of American constitutionalism. At the same time that concerned citizens will recognize how much they owe Trump for helping to bring about these breakthroughs, they will consider that he was delivering on a strategy pursued by the American conservative movement for more than half a century.

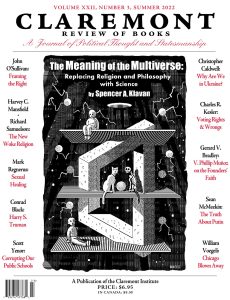

It took a long time for the elements of this strategy to be assembled, and for fortune to cooperate by aligning judicial openings with judicial talent and a GOP majority in the Senate; not to mention, with the wholesale philosophical education in originalism and natural law jurisprudence that conservative lawyers and judges needed, and still need. We know better than to count our chickens before they hatch. But so far, it’s been a very good year. Claremont Review of Books w Summer 2022 Claremont Review of Books, Volume XXII, Number 3, Summer 2022. (Printed in the United States on August 9, 2022.) Published quarterly by the Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy, 1317 W. Foothill Blvd, Suite 120, Upland, CA 91786. Telephone: (909) 981-2200. Fax: (909) 981- 1616. Postmaster send address changes to Claremont Review of Books Address Change, 1317 W. Foothill Blvd, Suite 120, Upland, CA 91786. Unsolicited manuscripts must be accompanied by a self-addressed, stamped envelope; or may be sent via email to: claremontreviewofbooks. com/contact-us.

Send all letters to the editor to the above addresses.

Download from: