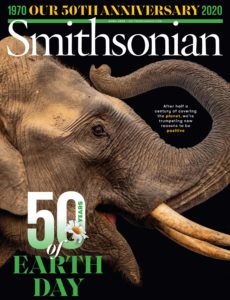

Smithsonian Magazine – April 2020

English | 115 pages | pdf | 112.42 MB

Welcome at Smithsonian Magazine April 2020 issue

N EARLY 1970, an advertisement for a new magazine promised it would examine the circumstances that shape the life of a human being—“this harassed biped,” who faces “staggering problems . . . from oil spills to famine.” Wildlife was in decline. Pollution was on the rise. An energy crisis loomed. “Our articles will probe man’s disasters,” the ad continued, “and join the battle for his improvement.”

Never mind the paternalistic “man,” “battle” wasn’t quite the right word, either: The magazine would always strive to be nonpartisan. Still, the first issue popped up right in the midst of the cultural havoc of the first Earth Day, and many of the concerns and ideals behind that nationwide protest also inspired the editorial team who launched Smithsonian. Justice was one guiding ethic. In the inaugural issue, the pioneering black scholar John Wesley Blassin game, acknowledging “the juggernaut of white supremacy,” documented the emergence of African-American studies on the nation’s campuses. But it was “Life Is an Endless Give-and- Take With Earth and All Her Creatures, ” an essay in the same issue by René Dubos, a renowned biologist and writer, that articulated the magazine’s point of view: “The optimist has good historical reasons to justify his confidence that the present environmental crisis will eventually be

overcome,” he wrote. There has indeed been progress. The Clean Air and Clean Water Acts soon became law, and the nation’s natural resources as well as its people have been better off ever since.

Smithsonian Magazine, meanwhile, has grown more than tenfold in print, to some 1.6 million paid subscriptions today, and there are another 8 million monthly readers online at Smithsonianmag.com, a publishing technology that didn’t exist, and wasn’t fully imagined, when the magazine debuted. Over those five decades Smithsonian has provided millions of dollars to the Smithsonian Institution in support of its mission, “the increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

The magazine (or “unmagazine,” as some wags used to say, because it eschewed trendiness) covers subjects far beyond environmental problems, and not every one of our more than 4,700 feature articles has aged well (see the 11-page spread from 1980 defending seagulls against the “rotten press” they receive ). Yet the magazine continues to explore, optimistically, the challenges and discoveries that promise to shape the lives of bipeds, quadrupeds and every other creature on Earth.

IT WOULD PRESENT art, since true art is never dated, in the richest possible reproduction.” That’s how Edward K. Thompson, the founding editor of

Smithsonian, once described the magazine staff ’s approach to pictures.

So when the current art and photography editors buried themselves in the archives in preparation for this anniversary issue, it came as no surprise that we found lots of wonderful art. What did surprise us, however, was just how artistic, how modern and how forward-looking the images in the first 50 years truly are.

Out of tens of thousands of images published in these pages over the last half-century, we selected a few hundred, hoping to find one that would sum up the magazine’s unique visual history. An absurdly difficult task, to be sure. Would it be an image from nature? Speckled-orange and green striped brittle sea stars on a coral reef from 1981 would do the trick. It’s got beauty, surprise, rarity. Or what about an X-rayed calla lily from 1986, as stunning as a Georgia O’Keeff e drawing? It embraces technology and nature, a couple of our favorite subjects. Then there are the red, blue and black seemingly Cubist drawings, published in 1974, that the illustrator and cartoonist Saul Steinberg had scribbled on Smithsonian Institution letterhead while serving as an artist in residence. Or how about George Booth’s 1991 cover cartoon of howling dogs? Wouldn’t that underscore the magazine’s tradition of commissioning prominent illustrators and photographers to create original new work?

No, an impossible task.

So we decided instead on five pictures, all from the magazine’s first decade, each touching on a theme. They certainly call attention to Thompson’s dictum that real art doesn’t have an expiration date. Beyond that, we think they express another important idea. There is art in science, there is art in the everyday—“the world offers itself to your imagination,” the poet Mary Oliver famously wrote—if only you look, really look.

Download from: