Reason Magazine March 2024

English | 68 pages | pdf | 22.02 MB

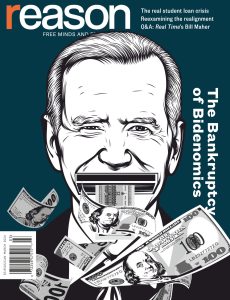

NOSTALGIANOMICS IS BACK. The White House and its proxies crow that the economy has never been better—and are greeted by skepticism from Americans who feel like life is less affordable than it was pre-pandemic. (To see why those Americans have a point, read “The Bankruptcy of Bidenomics,” page 20.) Meanwhile, GOP politicians and partisans capitalize on this pervasive sense of economic unease to campaign for President Joe Biden’s removal. In many cases, unfortunately, the call from the right is for something more than a return to pre-pandemic conditions. Many Republicans are falling back on a deeper and persistent form of historical revisionism.

What these conservatives—along with an interesting subset of technocratic progressives—are selling is a return to an imagined economic golden age. While the specifics are strategically blurry, it is generally pinned somewhere in the 1950s, or perhaps 1960, in the United States. In its most meme-ified form, it is an image of a well-groomed lady smiling at her blue-collar husband over text that reads something like: “Once upon a time, a family could own a home, a car, and send their kids to college, all on one income.”

The tricky thing about this claim is that it is in many senses true, but it is much more of a statement about culture than economics, and it is utterly misleading about the relative economic conditions of Americans today vs. midcentury. Americans were objectively much poorer in 1960 than they are today. That isn’t because of anything Biden did; it’s because of six decades of progress. Homeownership rates haven’t changed much since then, ticking up slightly: 62 percent in 1960 compared with about 66 percent today. What has changed dramatically are the homes themselves. New houses built in 1960 were about 25 percent smaller than new houses today and lacked many features we would now consider standard, such as laundry machines, dishwashers, and air conditioning.

The square footage per person was nearly a third of what it is today. In the immediate postwar period, it was actually illegal to build a house with more than one bathroom, due to copper shortages.

In 1960, there were four vehicles for every 10 Americans and about a quarter of households had none at all. Today there are about twice as many vehicles per capita. In other words, that 1960s family may have had one car, but they certainly didn’t have two. And that car was more prone to breakdowns and blowouts and was generally less reliable. It certainly didn’t have Bluetooth or Google Maps. College is objectively more expensive today. College educations are much more likely to be debt-financed as well. But in 1960, only about 45 percent of kids who finished high school went on to college, compared with 60 percent today. Far fewer kids finished high school as well, meaning that for most people the question of whether they could afford to send their kids to college didn’t even come up. College is also a much more gold-plated experience than it once was, in part due to rising expectations about standards of living that also inflate the other costs in this equation. As for that single income, it was often by necessity. Wages for some segments of the population, including the smiling white man of the memes, were kept artificially high thanks to pervasive discrimination that made many jobs inaccessible to large numbers of would-be workers, including that smiling woman from the memes—not to mention black Americans and immigrants, who were much more likely than their white counterparts to rent, to be carless, and to live in two-earner households even in 1960, never mind college.

PERHAPS THE MOST devastating rebuttal to nostalgianomics is that the life depicted in the meme is, in fact, available to most families right now. A married couple with kids can absolutely live in a small house with a single, less reliable car and fewer labor-saving conveniences and luxuries, while sending (maybe?) one of their kids to college—and they can do it on a single income. This is not what most people choose. To be fair, there are many ways public policy is nudging Americans away from those choices. Several forms of housing that were cheap and ubiquitous in the 1950s are now illegal, or very nearly so. Single-roomoccupancy buildings, for example, are banned in many American cities, making it harder to live cheaply when you are young to save for even a small house. And the cheapest new houses available for sale in 1960 lacked more than just air conditioning. In 1960, about 16 percent of Americans still lived in houses without indoor plumbing. Good luck getting an outhouse past a zoning board these days. Even a clothesline is tricky in some places in 2024. Late-model cars must comply with environmental and safety standards that raise the price of even the most basic models, not to mention the hefty tax hit on both the purchase of a car and the fuel you’ll need to drive it. And there are likely more requirements to come, including privacy-infringing tech (“Big Brother in the Driver’s Seat,” page 12). There

is almost certainly more demand for bottomof-the-line vehicles than it is legal for manufacturers to supply. Higher education debt is increasingly unmanageable thanks to irresponsible federal grant and loan policies that nudge students to take on debt that they can’t reasonably repay (for more on that, see “The Real Student Loan Crisis,” page 27) as well as

ballooning administrative costs. Still, the primary barrier to living in the style of the 1960s single-earner middle-class family is our own increasing standards. There are, of course, some rock-ribbed cultural conservatives who would gladly make all of these tradeoffs and more to return to the mores of the postwar period, all in the name of making America great again. But most people who dimly sense that the nostalgianomics memes are onto something wouldn’t tolerate the economic or social conditions that made it possible, nor would they support the policy changes required to bring it about. Among Americans who tell pollsters they are worried about the state of the Biden economy, one of the most commonly cited concerns is the cost of groceries. For the housewife in 1960, grocery prices would have been a major preoccupation; about 17 percent of her household’s disposable personal income was spent on food. That number fell below 10 percent for much of the 2000s. It recently popped up to nearly 12 percent, thus the skepticism when Biden smiles and says everything is going great. But a return to the 1960s would exacerbate, not relieve, the household economic anxiety that plagues the

Biden economy

Download from: