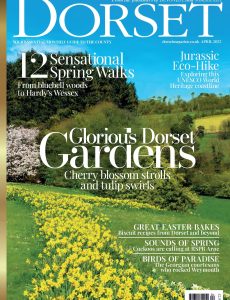

Dorset Magazine – April 2023

English | 117 pages | pdf | 93.91 MB

‘Wen birds do zing, an’ we can zee

Upon the boughs the buds o’ spring, Then I’m as happy as a king,

A-vield wi’ health an’ zunsheen.’

In his poem, The Spring, Dorset dialect poet William Barnes (1801-1886) brilliantly captures the unbridled joy of observing spring’s arrival in the Dorset countryside. But an English spring is an elusive thing. Perhaps that is why, when it does make an appearance, we are so enchanted by it. Certainly, poets wax lyrical about hosts of golden daffodils and a chaffinch singing its heart out on an orchard bough (right). And this edition of Dorset magazine is very much immersed in the arrival of spring and getting out and about to enjoy it.

From mid-January, on my daily dog walks, my eyes are scanning for signs of spring. Snowdrops are my first marker; this is swiftly followed by banks of pale-yellow primroses basking in the weak February sunshine. The silky silver buds of pussy willow, shivering catkins like golden waterfalls, and swelling buds on the trees are all indications that nature is emerging from its winter slumber. Even the dawn chorus has a greater sense of urgency as birds musically stake their territorial claim and a mate. What I am noting on my daily walks is phenology – from a Greek word meaning ‘to show, to bring to light, make to appear’ – the study of seasonal changes in plants and animals. And, are they appearing earlier or later than the previous year?

Robert Marsham (1708 -1797), an English naturalist based in Norfolk, is the founding father of phenology in this country. He regularly corresponded with the parson-naturalist Gilbert White, and they compared notes about the effects of the seasons on plants and animals. From 1736 to 1796, Marsham kept meticulous phenological notes called Indications of Spring. He measured 27 different signs of the season, including the first snowdrops, swallows, butterflies and cuckoo calls. His descendants continued these observations right up until the 1950s. Realising that this record keeping provided a valuable baseline from which seasonal change could be measured, the Meteorological Society launched its own phenology network across the UK in the 1870s. Some 300 years and 3 million records after those first observations by Marsham on his Norfolk estate, you can now take part in these annual observations via the Woodland Trust’s Nature Calendar. To date this citizen science project has more than 4000 participants. Join in at naturescalendar. woodlandtrust.org.uk.

Is our spring earlier? The simple answer is yes, probably by about a week, and the growing season on average is about five weeks longer than in the 19th century. But as we know spring is a fickle mistress. So, the traditional start of the English asparagus season on St George’s Day (April 23), is still subject to weather conditions. Things remain fluid about when spring truly settles in each year. I’m sure you will observe whether it has arrived in Dorset yet if you set out on one of the 12 wonderful spring walks in this edition. Whether it’s hearing the first cuckoo (possibly at RSPB Arne), spotting the first swallow, or tasting that first tender green asparagus spear. .. spring is surely very close to being sprung. •

Helen Stiles

Editor,

Dorset Magazine

Download from: